How do smartphones work out what direction they are pointing?

Sophisticated smart phone applications such as maps or augmented reality use measurements of the Earth's magnetic and gravity fields to work out the orientation of the phone.

Input latitude and longitude values in the tool below, or click anywhere on the map, to see how far off geographic north your compass would be at an altitude of 0km for today's date. The dark arrow indicates where your compass would point based on the High-Resolution World Magnetic Model (WMM) 2025.

A typical smart phone has three magnetic field sensors, fixed perpendicular to each other, which are used to work out the local direction of Magnetic North.

In addition, they have three accelerometers which sense gravity to give tilt information and to help work out which way is down.

Map Tiles © Esri — Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, TomTom, Intermap, iPC, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), and the GIS User Community

Three steps to your true path

-

1.

Magnetic and gravity field sensors located within your phone measure the direction of Magnetic North and the downward direction at the phone's location (Figure 1).

-

2.

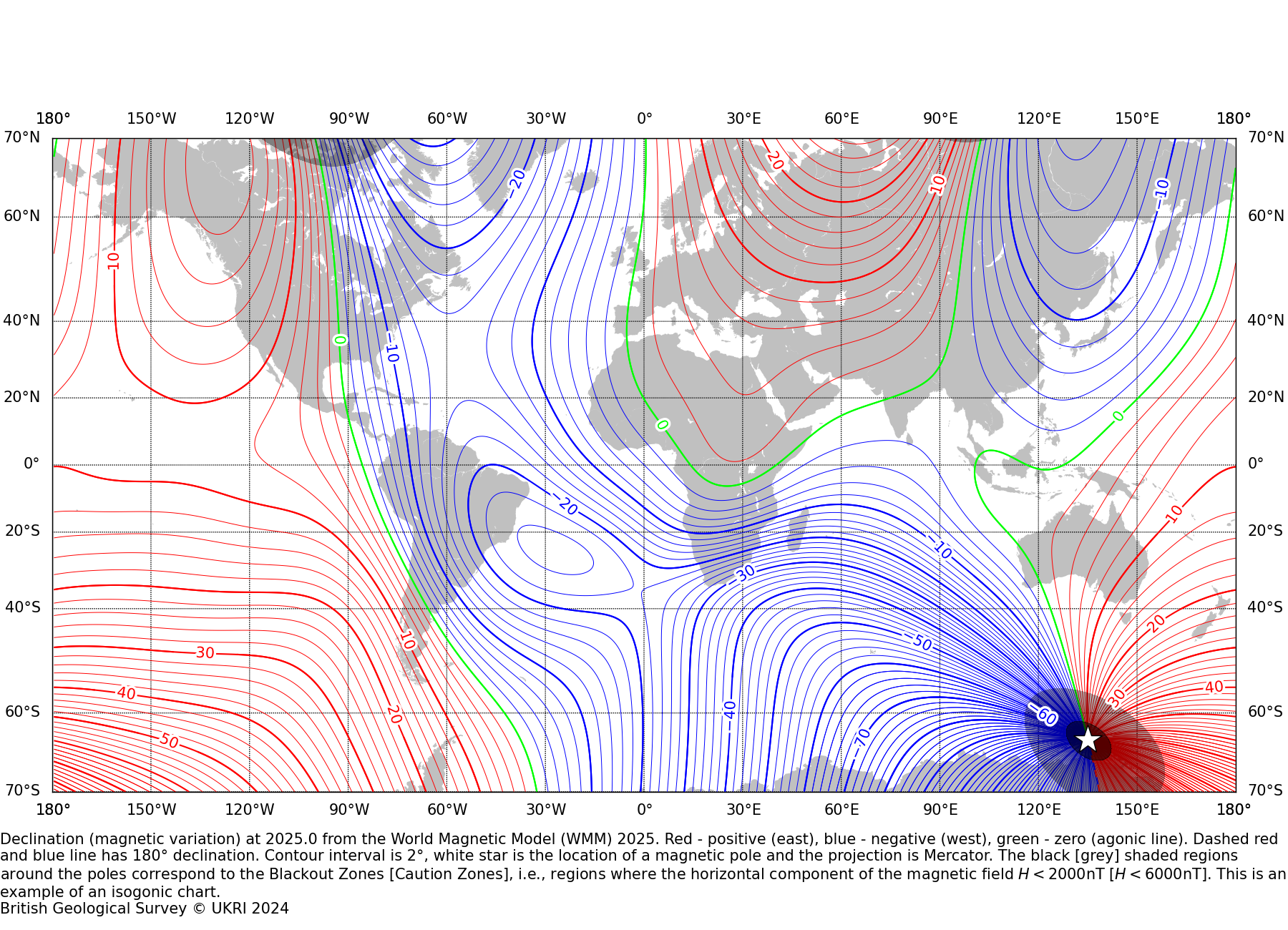

Using the GPS coordinates of the phone location and a global map of declination angle (the angle between true north and magnetic north), the application software computes the required correction angle for True North (Figure 2).

-

3.

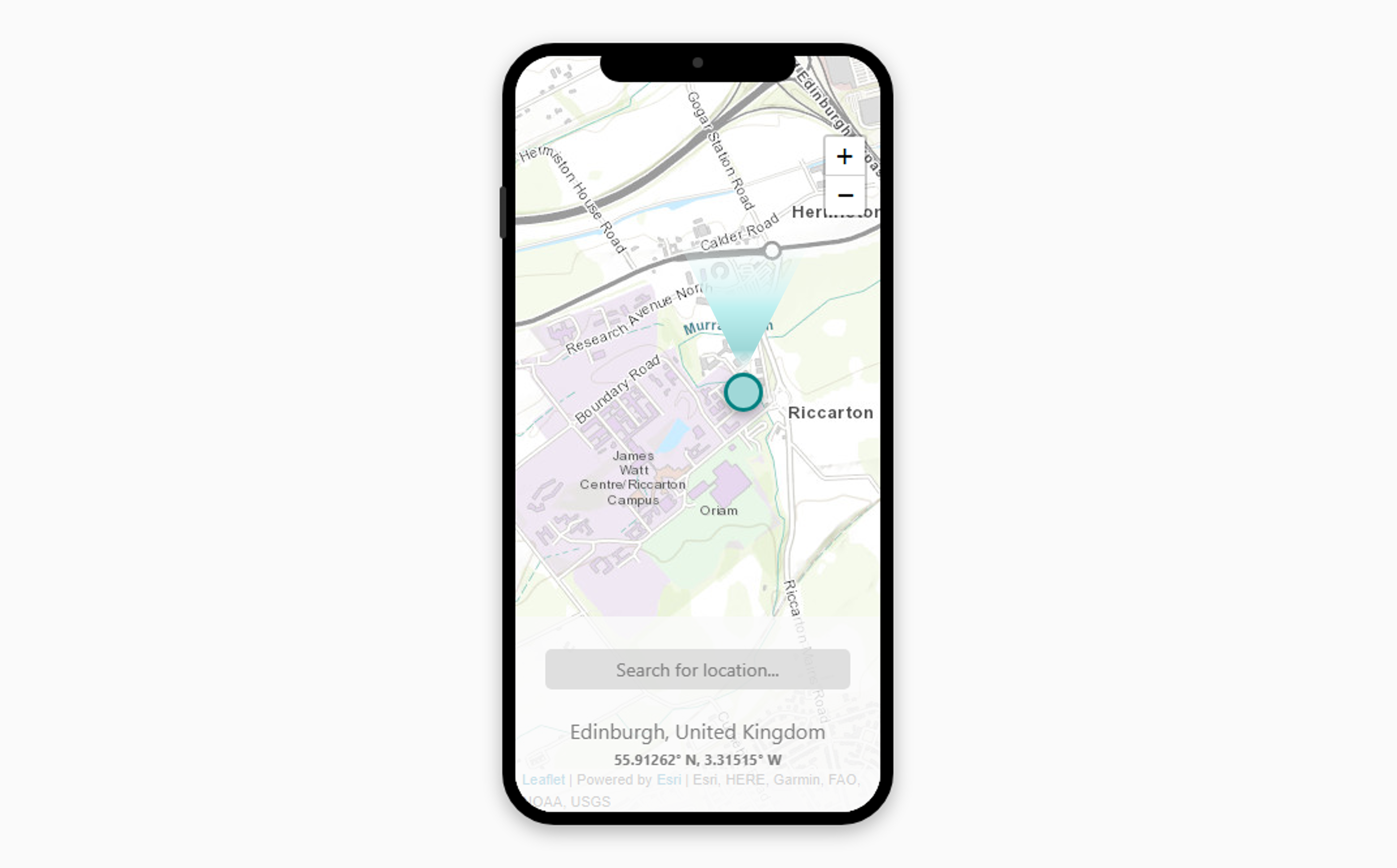

The map or image shown to the user can now be correctly orientated to True North, which is what most people expect (Figure 3).

Map Tiles © Esri — Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, TomTom, Intermap, iPC, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), and the GIS User Community

Why is it important?

The declination angle is small in the UK (< 2°) but can be much larger in California (~15°) or in Brazil (> 20°). Users in these areas would quickly become lost if the application software didn't correct for declination.

The World Magnetic Model also predicts secular variation (SV). Declination not only changes in space, but also in time, hence the need for the WMM to be updated every 5 years.

It is important that predictions of SV are as accurate as possible in order to minimise the effects of these temporal changes on navigation systems.